Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI) and Labral Tears of the Hip

Written by Dr. Eric C. Makhni

Sports Medicine, Orthopedic Surgery

Henry Ford Health System

West Bloofield | Troy | Sterling Heights

What is FAI?

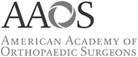

FAI, also known as femoroacetabular impingement, is a condition that can cause pain and disability in the hip joint. It is primarily due to an irregularity of the bones of the hip joint. The two main bones are the femur and the acetabulum, which form a “ball and socket” configuration.

Normally, the head of the femur comprises the “ball,” and the acetabulum comprises the “socket” of the hip joint. Both of these structures are covered by cartilage, which helps the bones glide by each other smoothly. The acetabulum is additionally surrounded by the labrum, which resembles a bumper and helps stabilize the hip joint. The figure on the right shows the normal anatomy of the hip joint.

Hip Joint Anatomy

(image courtesy of orthoinfo.aaos.org)

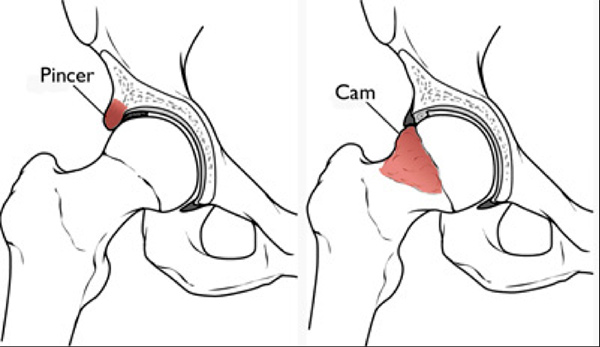

When either the head of the femur or the acetabulum (socket) has an irregularity, there can be “impingement” of the structures during certain motions or positions. This is known as femoroacetabular impingement, or FAI. There are three main types of FAI: cam, pincer, and mixed types. This impingement can cause pain by damaging the soft tissue structures of the joint, including the cartilage and labrum.

In cam impingement, there is an irregularity of the femur bone, resulting in a deformity of the area where the head of the femur joins with the neck of the femur. Therefore, the head of the femur is not round, and as it rotates in the joint, it can cause damage to the cartilage surfaces of the hip, as well as to the labrum.

In pincer impingement, there is an irregularity with the shape of the “socket,” or the acetabulum. This causes damage to the labrum as the hip is flexed and rotated, with the labrum getting pinched between the bony structures.

The third type of impingement is “mixed” type, in which is there is deformity of both the femoral head and the acetabulum. In these instances, there is often damage to both the cartilage surface and the labrum.

Types of Impingement

(image courtesy of orthoinfo.aaos.org)

While many causes of FAI are unknown, there are certain childhood conditions that may predispose patients to developing FAI. Additionally, many people are born with certain types of anatomy that also place them at higher risk for experiencing FAI. At this time, it is still unknown to what extent FAI can progress to osteoarthritis of the hip, but there is evidence to suggest that continued injury to the hip joint may progress to arthritis in some patients.

Patients with FAI may have hip pain that is present during certain positions or motions, such as with the hip flexed and rotated inwards (internal rotation). This pain is often in the groin, but can be present in the buttocks or side of the thigh as well. Many patients complain of a dull or throbbing ache, while others complain of a stabbing pain. Patients may have pain after being in a seated or sitting position for a prolonged time, or during certain twisting or squatting maneuvers. Some patients may have pain throughout the day, even with basic movements or activities, while others may only have pain during strenuous or athletic activities. This pain may contribute to development of hip stiffness in certain patients. Others may feel that they walk with a limp because of their injury as well.

How is FAI diagnosed?

Unfortunately, many patients may live with FAI for several weeks, months, or even years before they are finally diagnosed with the condition. This is due to the numerous different possible conditions that can result in hip pain, such as low back pain, nerve root irritation or impingement, or other processes of the pelvis or thigh.

Patients with possible FAI or other hip pathology should seek consultation with a provider knowledgeable about the hip joint. It is our experience that most diagnoses of FAI can be made through a comprehensive history and physical examination.

As stated above, patients often have characteristic symptoms that suggest presence of FAI (e.g. groin pain while getting into a seated position in a car). The history can be completed with a thorough physical examination. There are a number of exam maneuvers that we rely upon in order to establish the correct diagnosis.

In addition to the history and physical examination, there are additional tools that can help confirm the diagnosis of FAI. One of these tools consists of radiographic imaging. These can be in the form of x-ray, CT scan, and MRI scan.

X-rays are very powerful imaging tool, and it is our practice to obtain these images during your first visit to see us. X-rays are helpful in observing the bony anatomy of the hip joint and can often help determine why a patient has FAI. Moreover, we are able to measure the exact degree of deformity present in either the femoral head or the acetabulum using specialized computer tools. These measurements help us determine how much surgical correction is required in patients who undergo hip arthroscopy.

Bilateral CAM impingement in a 21 year old male

(image courtesy of Dr. Eric Makhni)

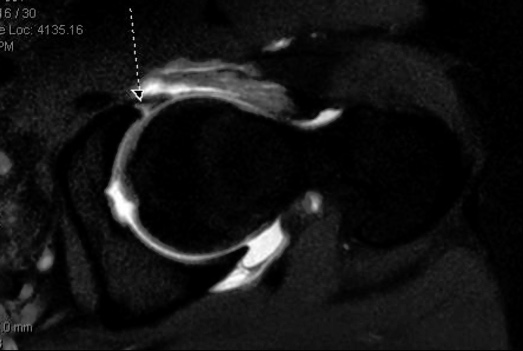

While the x-rays are helpful in giving a “bird’s eye view” of the anatomy of the hip joint, we will often get specialized (“advanced”) imaging to get better detail of the disease process in patients with FAI. One common tool is an MRI scan. In these scans, patients will typically be placed into a large scanner that is either a tube or donut-shaped. MRI’s help provide valuable information about the soft tissue structures of the hip joint, such as the acetabular labrum or the cartilage surfaces. Occasionally, the radiologist will inject a special solution called gadolinium, which is a fluid that “lights up” in MRI images. This fluid helps us determine precisely where the labral tear is, and how big it is.

Labral tear on MRI in a 16 year old girl

(image courtesy of Dr. Eric Makhni)

Finally, in many patients who will require surgery for their FAI or labral tears, we will perform a CT scan, or “computed tomography.” This type of imaging focuses on the bony anatomy, just like the x-ray does. However, it provides significantly more detail than a conventional x-ray. In fact, it provides such good detail that it is able to compose a 3-D reconstruction of the hip joint, providing the surgical team with a map of exactly where the bony deformities are and how best to correct them. The CT scans are usually performed only in patients requiring surgery as a pre-operative planning tool.

You may be asked to undergo a CT scan prior to surgery so that the surgical team can study the 3D images for optimal results.

Three-dimensional CT scan image ("cat scan") of a CAM deformity on the femoral head/neck junction (

(Image courtesy of Dr. Eric Makhni)

How is FAI treated?

As our knowledge about FAI improves, so do our treatment options. Thankfully, most patients with FAI do not need surgery in order to get better. There are a number of different treatment options that may help patients feel better without being invasive!

The first line of treatment in FAI consists of rest, anti-inflammatory medications, and physical therapy. It is our experience that most patients improve with these treatments alone, going on to live active and satisfying lifestyles. We recommend patients avoid activities or positions that cause pain or discomfort while treating symptoms with anti-inflammatory medications (as long as you don’t have any medical conditions that prevent you from taking these medications!) and ice treatment. We have also found that physical therapy can be very effective in treating hip conditions by improving the core musculature, hip stabilizers, and gait training.

In patients who do not get better with medications rest, and physical therapy, we may try to better understand the injury by obtaining specialized imaging, such as an MRI (with or without contrast fluid in the joint). This helps us determine if the hip injury is within the joint (such as with FAI or labral tears), or if the injury is outside the joint (such as irritation or injury to the surrounding tendons, muscles, or structures).

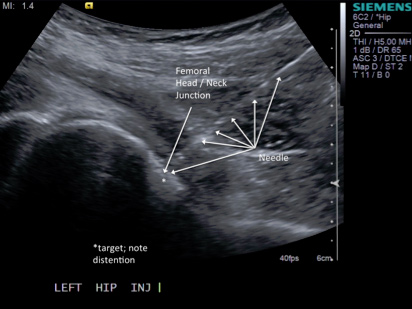

Once this information is obtained, some patients may benefit from undergoing an injection directly into the hip joint. These are called intra-articular hip injections. These may be performed by trained providers, such as physicians or certified physician assistants (PA-C), under fluoroscopic (x-ray) or ultrasound guidance. The injections are typically performed in the office and do not require any anesthesia or other medications.

Most injections consist of a combination of an anesthetic and cortisone. The anesthetic often causes immediate pain relief, but it is only short lasting (a couple of hours). The cortisone usually takes 1-2 days to set in but can hopefully provide pain relief for many days, weeks, or even months through its anti-inflammatory effects.

Hip injections can be both diagnostic and therapeutic.

They are therapeutic if they result in decreased pain and disability, as this is one of the main goals of undergoing a hip injection. However, they are also diagnostic because they tell us if your pain and symptoms are coming from inside the hip joint, or if they are actually coming from somewhere else. Therefore, patients who respond favorably to an intra-articular injection may have a higher likelihood from benefiting from hip arthroscopy compared to those who do not.

Image of ultrasound-guided hip injection.

(image courtesy of www.mskultrasoundprocedures.com)

Finally, in patients who do not experience lasting pain relief from these non-operative treatments, surgery may be considered. In treating FAI, the mainstay of surgical treatment consists of addressing both the labral repair as well as the bony deformity that caused the labral repair. Surgery is performed arthroscopically, using state-of-the-art minimally invasive technology.

Surgical Options for FAI

There are a number of different surgical options for patients with FAI who do not adequately improve with non-operative treatment. Ultimately, the type of surgery required depends on the underlying anatomy and deformity of the hip joint. In patients with significant bony deformity, surgery must be able to fix the deformity and recreate a joint with normal alignment. This can only be done with open surgery.

For most other patients who have only a mild deformity resulting in FAI, hip arthroscopy is an excellent surgical option. Current arthroscopic techniques allow for reliable visualization and correction of the bony deformities of the femoral head and acetabulum, as well as precise repair of the torn labrum. Because hip arthroscopy is minimally invasive, patients may go home the same day following surgery, without having to be admitted to the hospital for overnight monitoring.

Certain patients who have both large bony deformities and labral tears may actually undergo a combined surgery, in which a hip arthroscopy is performed to fix the labral tear followed by an open surgery to correct the bony deformity.

Hip Arthroscopy for FAI

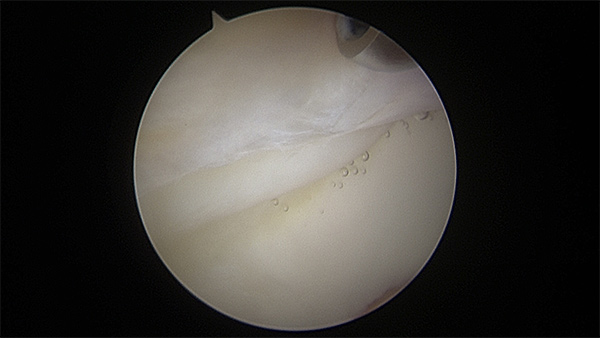

Thankfully, most cases of FAI that require surgery can be successfully treated with arthroscopic surgery. Hip arthroscopy is a minimally invasive surgical technique that utilizes two or three small incisions to adequately view and treat the underlying bony deformity and labral tear. Any loose flaps of cartilage can also be cleaned or repaired at that time.

During hip arthroscopy, the patient is given general anesthesia and is fully asleep during the procedure. After anesthesia is performed, the patient is positioned onto a specialized hip arthroscopy table, with the feet secured in fitted boots. A post is used between the legs and the legs are placed into traction, thereby opening the space between the bones of the hip joint in order to allow safe insertion of arthroscopic cameras and instruments. The first part of the procedure consists of inspecting the hip joint (diagnostic arthroscopy), followed be removal of the acetabular deformity (pincer resection) and treatment of the labral tear. This treatment usually involves a repair of the labrum using suture anchors, however sometimes the labrum may just need to be debrided, or “trimmed” and may not require a full repair.

After the first part of surgery is complete, the traction is removed from the legs and the arthroscopic cameras and instruments are moved from inside the joint to just outside the joint. This location is called the “peripheral compartment.” It is from here that we are able to correct the bony deformity on the femoral head and neck.

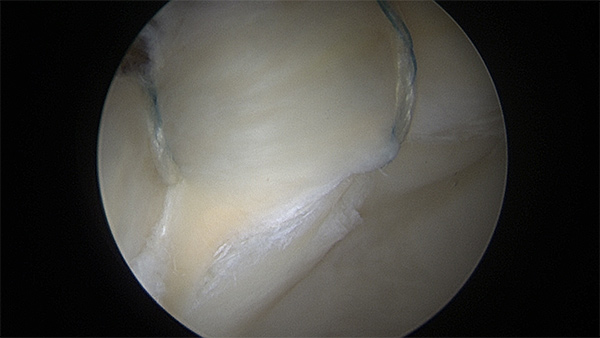

Labral tear in the right hip of a 20 year old female college athlete. Notice the bubbling of the cartilage ("wave sign").

(Image courtesy of Dr. Eric Makhni)

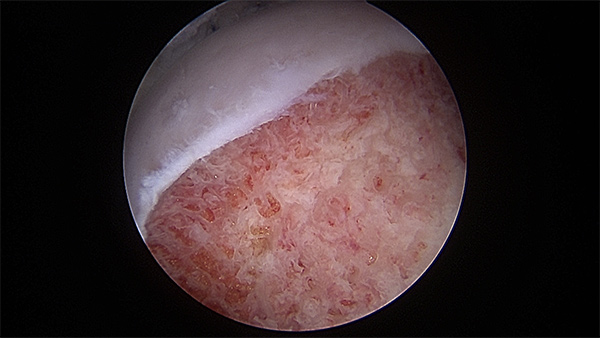

Repair of the torn labrum in the same 20 year old female college athlete

(Image courtesy of Dr. Eric Makhni)

Evidence of CAM impingement in a 23 year old patient with labral tear

(Image courtesy of Dr. Eric Makhni)

Resection of CAM deformity in same 23 year old patient

(Image courtesy of Dr. Eric Makhni)